What animals taught me about queer life and hope

Stephen Quandt shares his story.

Written by Stephen Quandt

I never would have predicted that two cats would finally and fully connect me back to my closeted gay life as a teen in the 70s and my hope for a meaningful life.

There were many fine things about growing up as a teen in suburban New Jersey in the late 70s, but being gay wasn’t one of them, at least not for me.

I decided at the time it was way too soon to admit I was gay, or in the terminology of my peers, a “homo.” I started waiting for that mythical moment when all of a sudden, girls wouldn’t be boring, and guys wouldn’t be exciting. But that moment didn’t come. But I still couldn’t say I was gay, I couldn’t even say I was bi. I was utterly disconnected from what I was feeling, and at the same time, terrified of being found out.

That didn’t stop me from falling in love with one of my best friends at around age 16, a friend who I never had any sexual experience with, then or later. There were plenty of deeply sensual experiences, a hug, the accidental touch of my finger to his, any number of casual, seemingly incidental, bodily appendage embraces. But still I wasn’t gay and I couldn’t be gay.

I was stuck in this in-between world, where I was unable to imagine a romantic future for myself. In all my teen years, I never daydreamed about a future with another guy. Daydreams about sex daily, but no dreams about a life. No house, no picket fence, no partner, no boyfriend, no dating. Obviously no thoughts about marriage or having children, that was probably off the table of imagination for most of us back then.

This wasn’t helped by the lack of a future mirrored back to me by family, television, film, advertisements in print or elsewhere, and maybe theatre, in that order. There was nothing for me to see, nothing positive. My parents were opposite sexed, and in the arts, gays were depicted as clowns or criminals, and that was about it. I had nothing to help spark my imagination, to tell me what was possible, to show me a future.

What I also learned is that I had failed myself as a teenager. I had so many opportunities to come to terms with who I was and I failed each and every one. A gentle question from my mom, another question from that friend whom I was in love with, and one day an observation from a school buddy who noticed that when I got high on weed I became a little effeminate.

A cat named Petunia

My life completely changed forever in May of 2011 when I went out on my first “case” as a volunteer with the ASPCA’s Field Investigation and Response Team to the site of the Joplin, Missouri tornado - an EF 5 tornado that killed hundreds of people, destroyed an entire town and left more than 1,200 dogs and cats homeless.

When I arrived in Joplin, I was a theatrical lighting designer who volunteered in animal welfare. When I left Joplin, I was on a path to becoming a professional in animal welfare.

What changed in me is something that isn’t generally taught or experienced under the professional level (except for health care providers, ministers, and therapists as examples). I learned what it means to relieve suffering in other beings, in this case a cat, who couldn’t speak for herself.

This cat - whom I named Petunia - was terrified. She couldn’t interact with people at all.

I spoke to her gently, every day, until finally one day - in an instant - she blossomed into the very friendly cat that she really was, but to me alone.

With more time she warmed up to everyone, and in time got adopted. She came out so to speak. Her unspoken thought: “I made it, I’m alive again, thank you!” being said by both of us at the same time.

The experience of relieving her suffering was so powerful that I struggle to describe it. In animals that can’t speak for themselves, relieving their suffering is experienced as a gift they give back to you, selflessly, a wave of compassion and communication from them to you and back to them, a type of love that flows in both directions at the same time. All of a sudden they have a voice, and it is pure love.

A cat with no name

In my career in animal welfare we get what is sometimes called “compassion fatigue” but is more accurately called “vicarious trauma” - we don’t get tired of being compassionate, we get tired and hurt bearing witness to pain and suffering. The things that people have done to their animals.

There was a day last year, where something happened and I reached a new breaking point.

A member of our rescue team had just arrived with a cat, and not knowing what to expect, I asked if I could help. The cat was in a box inside her vehicle.

I didn’t know a cat could be this emaciated and still be alive. When you hear the phrase, “skin and bones” it literally meant just that. She couldn’t walk.

She was lying in a box that had been left outside a business. I don’t just mean randomly left next to a business, I mean the business boxed her up and dumped her by their building allowing her to be found by a passerby - in a box with their business name on it. A cat with no name.

She gently ate food when offered by my colleague, appearing grateful without being greedy, so very sweet and gentle. And dying. We had no choice. She had to be euthanised.

I cannot imagine the depth and the length of her suffering - at human hands. And at that moment I broke. I saw her end of life in my mind’s eye, I felt as much of her pain as I could feel not being her. It was as if I was experiencing her trauma, her wasting distress at the moment that she lay dying, and I couldn’t handle it. Vicarious trauma.

I went to see a trauma therapist.

What I learned with this therapist is that I’ve been trying to find futures for these wonderful creatures who know no future, who wait in a cage for something good to happen. I find futures for the cats when I, as a gay child, felt and saw no future.

In a way, I am all of them. All these cats, waiting for futures, for homes, for families. They are me now when I was young then. And now I am trying to pay it forward for them.

When I fail, or feel that I have failed an animal, as we - society - failed this cat, I am saddled with pain. It hurts so much. I feel that existential loneliness inside their burning distress. The future, her future at that precise moment, our futures, extinguished.

If you felt what I experienced when I helped Petunia, you too would likely be forever changed. But for the starving cat, the only relief to suffering was death. The opposite and antithesis of what I learned in Joplin.

Finding a future

This work that I do on behalf of and in service to animals, reminds me of one glorious thing, and that is our shared humanity. That same mirror of humanity that was denied to me as a terrified gay child. A humanity that was reflected back to me by a cat named Petunia, and a deeply painful humanity that I am reminded of every time I think of that starving cat in the box. The cat who had no name.

I grew up to get the life I always wanted but couldn’t imagine, a debt I owe to all the animals waiting in cages for their futures, yearning for better lives.

Stephen Quandt on How To Date Men

In a recent episode of the podcast, How To Date Men, Stephen Quandt discusses his personal reflections on "What animals taught me about queer life and hope."

In the conversation, we discuss trauma, closeted teens, and why adopting a pet could deliver the healing that you need.

About the writer

Stephen is a writer, author and certified feline behavior consultant with 20 years experience working with cats and dogs in the field and in shelters including the ASPCA where he worked in feline behavior, adoptions and rescue work and currently with the Animal Care Centers of NYC.

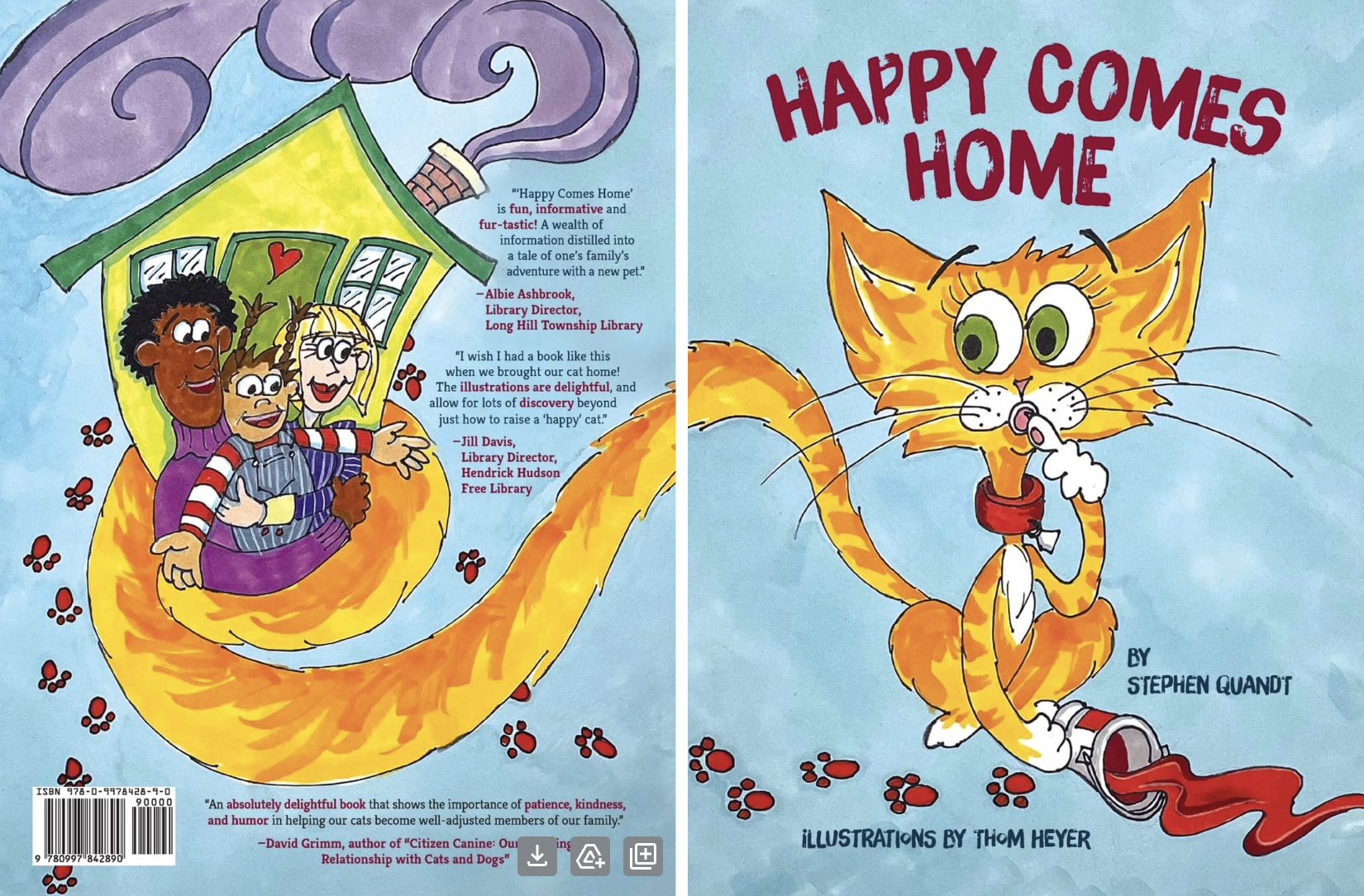

Stephen is the author of a new children’s book, Happy Comes Home and two webinars, Decoding the Mysteries of Cats, and The Dogs of Chernobyl: a Story of Hope and Resilience which he gives to the public through libraries as well as to NGOs, shelters, rescues, vet practices and companies. For more information, please visit Catbehaviorhelp.com and he can also be reached at stephen@catbehaviorhelp.com.

Across social media he can be found @catbehaviorhelp and on TikTok @cat_behavior_help. He is married to artist Thom Heyer who illustrated Happy Comes Home and they have two cats, blind-from-birth Jenny who rules their home and her bestie, Cricket.

The Dogs of Chernobyl

Stephen Quandt shares his experience of helping the pets that were left behind after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and the intriguing behaviour patterns developed by the dogs who have found a way to live without humans.

How do you get a cat to like you?

Stephen Quandt shares his insights about cat behaviour and how to get on the good side of our feline friends.

How's Your Gaydar?

Connect with guys near you.